How Does Stokes Law Explain Terminal Velocity in Fluids?

Stokes Law and terminal velocity represent core ideas in fluid mechanics, crucial for mastering JEE Physics. These ideas explain how objects move in fluids, why raindrops fall steadily, and how resistance shapes motion.

Understanding the Origin of Stokes Law

Stokes Law was formulated by Sir George Gabriel Stokes in 1851. It explains how a viscous fluid resists a sphere's motion, predicting how objects settle or fall through liquids.

Imagine dropping a small bead in honey. As it moves, honey resists its motion, creating a drag force. This visualizes the application of Stokes Law in daily life.

Stokes Law: Principle and Conditions

Stokes Law says that the viscous drag force on a spherical particle in a fluid is directly proportional to its radius, the velocity of movement, and the fluid's viscosity.

For Stokes Law to be valid, the sphere must move slowly. The flow must remain smooth without turbulence, and the fluid should extend infinitely in all directions.

Curious about other influences? Explore how Fluid Pressure Explained impacts fluid dynamics alongside viscosity.

Stokes Law and Drag Force Formula

The Stokes Law equation describes the drag force ($F$) acting on a sphere falling through a viscous fluid.

$F = 6\pi\eta r v$

Here, $F$ is the viscous drag force, $\eta$ is the viscosity, $r$ is the sphere's radius, and $v$ is its velocity. These variables define the fluid resistance encountered.

If the sphere's density differs from the fluid, gravity and buoyancy also act, leading to a net downward force influencing motion.

To study advanced boundary and surface effects, read about Understanding Surface Tension in Physics.

Derivation of Stokes Law

Stokes derived his law using the concept of balancing forces. For a sphere moving in a viscous fluid at low Reynolds number, the flow remains laminar.

Dimensionally, the drag force $F$ must depend on $\eta$, $r,$ and $v$, giving $F \propto \eta r v$. Experiments confirm the constant as $6\pi$, forming the classic law.

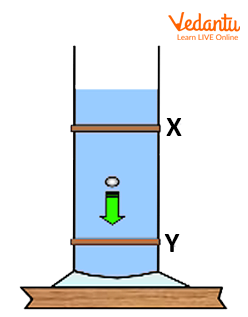

Visualizing a Sphere in Viscous Fluid

Picture a solid ball dropping through oil: resistance slows its downward journey. As the ball accelerates, resistance increases until it balances gravity.

This equilibrium point is when the ball achieves terminal velocity. For other motion insights, check out Particle Velocity Insights.

Formula for Terminal Velocity Using Stokes Law

Terminal velocity ($v_t$) is the maximum steady speed of an object falling through a fluid, when net forces become zero due to the balance of drag, gravity, and buoyancy.

For a sphere, terminal velocity is:

$v_t = \dfrac{2 r^2 (\rho - \sigma) g}{9\eta}$

Here, $\rho$ is the sphere's density, $\sigma$ is the fluid's density, $g$ is gravitational acceleration, and $\eta$ is viscosity. This formula is often used in sedimentation studies.

Key Differences: Stokes Law vs. Terminal Velocity

| Stokes Law | Terminal Velocity |

|---|---|

| Gives the drag force formula | Gives max steady speed |

| Depends on viscosity, radius, velocity | Result of zero net force |

| Applies at any instant | Applies after acceleration stops |

Derivation: Terminal Velocity in Fluid

As a sphere falls, its weight pulls it down while fluid drag and buoyancy push up, eventually balancing out to yield terminal velocity.

Net downward force is:

$F_g = \dfrac{4}{3}\pi r^3 (\rho - \sigma)g$

At terminal velocity, viscous drag equals the net downward force:

$6\pi\eta r v_t = \dfrac{4}{3}\pi r^3 (\rho - \sigma)g$

Solving for $v_t$ gives:

$v_t = \dfrac{2 r^2 (\rho - \sigma)g}{9\eta}$

Practical Examples: Observing Terminal Velocity

Common real-world displays of Stokes Law and terminal velocity include parachutists, raindrops, and small spheres settling in viscous fluids like glycerine or oil.

To understand the influence of gravity on such motions, dive into Concepts of Gravitation for JEE preparation.

Numerical Example: Terminal Velocity Calculation

A steel ball of radius $1$ mm falls through castor oil. The densities are: ball $= 8000$ kg/m$^3$, oil $= 900$ kg/m$^3$, viscosity $\eta = 0.6$ kg/m·s. Find its terminal velocity.

Known: $r = 1 \times 10^{-3}$ m, $\rho = 8000$ kg/m$^3$, $\sigma = 900$ kg/m$^3$, $\eta = 0.6$ kg/m·s, $g = 9.8$ m/s$^2$.

Use terminal velocity formula:

$v_t = \dfrac{2 r^2 (\rho - \sigma) g}{9\eta}$

Substitute values:

$v_t = \dfrac{2 \times (1 \times 10^{-3})^2 \times (8000 - 900) \times 9.8}{9 \times 0.6}$

Calculate numerator and denominator:

$v_t = \dfrac{2 \times 1 \times 10^{-6} \times 7100 \times 9.8}{5.4}$

Numerator: $2 \times 1 \times 10^{-6} \times 7100 \times 9.8 = 0.13916$

$v_t = \dfrac{0.13916}{5.4} = 0.0258$ m/s

Final answer: The ball's terminal velocity is approximately $0.026$ m/s through castor oil.

For further reading on how velocities change in fluids, see Particle Velocity Insights.

Factors Affecting Terminal Velocity

Terminal velocity increases if the object's radius, density difference, or $g$ increases. It decreases with higher fluid viscosity. Streamlined objects reach higher values than blunt shapes.

Real-World Applications of Stokes Law and Terminal Velocity

- Design of rain gauges and sedimentation tanks

- Meteorology: Study of raindrop fall and cloud particles

- Biomedical: Blood cell settling in plasma tests

- Industrial: Purification of oil, paints, or colloids

- Sports: Parachute and skydiving motion analysis

Want a deeper grasp of real-life uses? Visit Understanding Terminal Velocity for extended application insights.

Practice Question for Self-Assessment

A small plastic ball ($r=0.5$ mm, $\rho=1200$ kg/m$^3$) is dropped in glycerine ($\sigma=1300$ kg/m$^3$, $\eta=1.5$ kg/m·s). Will the ball rise or sink? Calculate terminal velocity using Stokes Law.

Common Mistakes in Applying Stokes Law

- Using the formula at high Reynolds number (turbulent flow)

- Neglecting buoyancy in fluids denser than the sphere

- Wrong units for viscosity or radius

- Mixing up density of fluid and object

Key Takeaways for JEE Physics Preparation

Stokes Law connects the forces on moving spheres in fluids to object properties and velocity. Terminal velocity marks the maximum speed where forces are balanced, making further acceleration impossible.

Mastering these concepts is vital for confidently tackling JEE Physics problems in mechanics and fluid dynamics. Understanding their real-world and exam-level relevance gives you an exam advantage.

Related Physics Topics for Next Steps

Fluid dynamics, Reynolds number, viscosity, buoyancy, drag coefficient, Bernoulli's Principle, laminar and turbulent flow, sedimentation, projectile in fluids.

FAQs on Understanding Stokes Theorem and Terminal Velocity

1. What is Stokes’ Theorem?

Stokes’ Theorem connects surface integrals and line integrals in vector calculus. It states that the surface integral of the curl of a vector field over a surface equals the line integral of the vector field around the boundary curve of that surface.

Key points:

- Relates curl, surface integrals, and line integrals

- Mathematically: ∬S (curl F) · dS = ∮C F · dr

- Essential in vector calculus syllabus and CBSE exams

2. What is terminal velocity?

Terminal velocity is the constant speed that a falling object reaches when the force of gravity is balanced by the force of air resistance (drag).

Main ideas:

- No further acceleration after reaching terminal velocity

- Depends on mass, shape, area, and fluid density

- Frequently asked in Physics CBSE board exams

3. State Stokes’ Law and write the formula for the viscous force on a sphere.

Stokes' Law defines the drag force experienced by a small, spherical object moving slowly through a viscous fluid.

Formula:

- Viscous force, F = 6πηrv

- η = coefficient of viscosity, r = radius of sphere, v = velocity of object

4. How is terminal velocity derived using Stokes’ Law?

Terminal velocity is derived by balancing weight, buoyant force, and viscous drag as per Stokes’ Law.

Derivation steps:

- Weight (W) = 4/3 πr³ρsphereg

- Buoyant force (B) = 4/3 πr³ρfluidg

- Stokes’ drag (F) = 6πηνrv

- At terminal velocity, W - B = F

- Solving gives terminal velocity: vt = [2r²g(ρsphere - ρfluid)] / (9η)

5. What is the significance of terminal velocity in practical life or applications?

Terminal velocity has many real-world applications.

Examples:

- Design of parachutes for skydivers

- Raindrops falling through air reach terminal velocity

- Settling of particles in fluids (oil, water purification)

6. What factors affect terminal velocity?

The terminal velocity of an object depends on several variables:

- Radius (r) of the object

- Density difference (ρobject - ρfluid)

- Acceleration due to gravity (g)

- Viscosity (η) of the medium

- Shape and surface area of the object

7. What are the conditions for applying Stokes’ Law?

You can use Stokes’ Law only when:

- The flow is laminar (Reynolds number < 1)

- The object is a small, smooth sphere

- The fluid is incompressible and viscous

8. What is the difference between Stokes’ Theorem and Stokes’ Law?

Stokes’ Theorem is a fundamental result in vector calculus, whereas Stokes’ Law relates to fluid mechanics.

- Theorem: Relates surface and line integrals using curl (Math)

- Law: Gives drag force on spheres in viscous fluids (Physics)

9. Why does a heavy object not keep accelerating while falling through a fluid?

A heavy object stops accelerating in a fluid when the downward force (weight minus buoyancy) is balanced by the upward viscous force.

The net force becomes zero and the object moves at terminal velocity.

10. When should you apply Stokes’ Law in numericals?

Use Stokes’ Law when asked about the viscous drag force or terminal velocity for slow-moving, small, spherical objects in a viscous medium.

Identifying clues:

- Mention of small spheres or droplets

- Keywords: “viscosity,” “laminar flow,” or “terminal velocity”

11. What is the mathematical statement of Stokes’ Theorem?

The mathematical statement of Stokes’ Theorem is:

∮C F · dr = ∬S (curl F) · dS

Where C is the closed boundary curve and S is the surface it encloses.

12. Explain what happens to terminal velocity if the viscosity of the medium is increased.

As the viscosity (η) of the medium increases, the terminal velocity of the falling object decreases because terminal velocity is inversely proportional to viscosity.

Mathematically: vt ∝ 1/η.