Important Laws and Applications of Magnetic Effects of Current

Magnetic effects of current and magnetism form a core part of electromagnetism, explaining the interaction between electric currents and magnetic fields. This topic covers the fundamental principles of how moving charges generate magnetic fields, as well as how materials respond to these fields. It is essential for understanding electrical devices, magnetization of materials, and various applications in physics.

Magnetic Field and Oersted’s Experiment

A magnetic field is defined as a region around a moving electric charge or a current-carrying conductor where magnetic effects are observable. Oersted’s experiment demonstrated that electric current creates a magnetic field, influencing a magnetic needle placed nearby.

When the direction of current through a conductor is reversed, the direction of deflection of a magnetic needle placed nearby also reverses. Increasing the current or reducing the distance between the needle and the conductor enhances this deflection.

Biot-Savart Law

Biot-Savart Law provides the expression for the magnetic field produced by a small current element. The magnitude of the field at a point is given by:

$dB = \dfrac{\mu_0}{4\pi} \dfrac{Idl \sin\theta}{r^2}$

Here, $I$ is current, $dl$ is the length element, $r$ is the distance of the point from the element, $\theta$ is the angle between $dl$ and $r$, and $\mu_0$ is the permeability of free space $(4\pi \times 10^{-7}\ \text{Tm/A})$.

In vector form, $d\vec{B} = \dfrac{\mu_0}{4\pi} \dfrac{I(d\vec{l}\times \hat{r})}{r^2}$, where $d\vec{l}$ is in the direction of current flow.

Applications of the Biot-Savart Law are further explained in detail in the Biot-Savart Law resource.

Magnetic Field Due to Different Conductors

The magnetic field at a point due to a straight current-carrying wire or a circular loop can be calculated using the Biot-Savart Law. For an infinitely long wire, the field at a perpendicular distance $d$ is $B = \dfrac{\mu_0 I}{2\pi d}$.

For a circular coil of radius $R$ carrying current $I$, at a distance $x$ along its axis, $B = \dfrac{\mu_0 I R^2}{2(R^2 + x^2)^{3/2}}$. At the center of the coil ($x=0$), this becomes $B = \dfrac{\mu_0 I}{2R}$.

For detailed derivations and variations, resources are available at Magnetic Field From Wire.

Ampere’s Circuital Law

Ampere’s Circuital Law relates the integrated magnetic field around a closed loop to the net current passing through the loop. Mathematically, it is written as:

$\oint \vec{B} \cdot d\vec{l} = \mu_0 I_{\text{encl}}$

This law is especially useful for calculating fields in symmetric situations, such as inside a long solenoid, around a straight wire, or within a toroid.

Magnetic Field Due to a Solenoid and Toroid

A solenoid is a tightly wound helical coil. The magnetic field inside a long solenoid is uniform and parallel to its axis and given by $B = \mu_0 n I$, where $n$ is the number of turns per unit length.

Outside the ideal solenoid, the magnetic field is considered negligible. At the ends, the field reduces to half of its value inside the solenoid.

A toroid is a solenoid bent into a ring shape. The magnetic field inside a toroid at a distance $r$ from the center is $B = \mu_0 n I$, with the field being zero outside and inside the empty central region.

Motion of a Charged Particle in a Magnetic Field

A moving charge in a uniform magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to both its velocity and the field, given by $F = q\vec{v}\times\vec{B}$. For a perpendicular entry, it describes a circular path of radius $r = \dfrac{mv}{qB}$ and period $T = \dfrac{2\pi m}{qB}$.

If the velocity has components both perpendicular and parallel to the magnetic field, the trajectory becomes a helix, with pitch $p = v_\parallel T$.

Force on a Current-Carrying Conductor in a Magnetic Field

When a current-carrying conductor of length $L$ is placed in a magnetic field, the force on it is $F = I L B \sin\theta$. The direction of this force is determined by Fleming’s left-hand rule.

Interaction Between Parallel Current-Carrying Wires and Definition of Ampere

Two long, parallel current-carrying wires separated by a distance $d$ exert equal and opposite magnetic forces per unit length on each other, given by $f = \dfrac{\mu_0}{2\pi} \dfrac{I_1 I_2}{d}$.

One Ampere is defined as the constant current which, if maintained in two straight parallel conductors placed 1 meter apart in vacuum, produces a force of $2\times 10^{-7}\ \text{N/m}$ between them.

Magnetic Dipole and Bar Magnet

A bar magnet behaves as a magnetic dipole with north and south poles. Its magnetic dipole moment ($\vec{M}$) is a vector from south to north, with magnitude $M = m \times 2l$, where $m$ is pole strength and $2l$ is the magnetic length.

Current loops and solenoids also act as magnetic dipoles, with moment $M = NI A$, where $N$ is number of turns, $I$ is the current, and $A$ is the area.

Torque and Potential Energy of a Magnetic Dipole

A magnetic dipole in an external uniform magnetic field ($\vec{B}$) experiences a torque $\vec{\tau} = \vec{M} \times \vec{B}$ and has potential energy $U = -\vec{M} \cdot \vec{B} = -MB\cos\theta$.

Maximum torque occurs when the angle between $\vec{M}$ and $\vec{B}$ is $90^\circ$, and potential energy is minimum when $\vec{M}$ is aligned with $\vec{B}$.

Moving Coil Galvanometer

A moving coil galvanometer is used to detect and measure small electric currents. The coil, suspended in a radial magnetic field, experiences a torque proportional to the current, producing a measurable deflection. Adding suitable resistances converts it to an ammeter or a voltmeter.

Magnetic Properties of Materials

Magnetic materials are classified as diamagnetic, paramagnetic, or ferromagnetic, depending on their response to an external magnetic field. Diamagnetic materials are weakly repelled, paramagnetic are weakly attracted, and ferromagnetic are strongly attracted by the field.

| Type | Main Property |

|---|---|

| Diamagnetic | Repelled, weak susceptibility |

| Paramagnetic | Weakly attracted, small positive susceptibility |

| Ferromagnetic | Strongly attracted, large positive susceptibility |

Magnetic susceptibility $(\chi_m)$ measures how easily a material is magnetized, while relative permeability $(\mu_r)$ characterizes how it conducts magnetic flux, with $\mu_r = 1 + \chi_m$.

Magnetisation, Permeability, and Curie’s Law

The intensity of magnetization $(I)$ is the induced magnetic moment per unit volume. Magnetizing field $(H)$ is the external field applied. Magnetic susceptibility $(\chi_m)$ relates $I$ and $H$ by $\chi_m = I / H$, and permeability $(\mu)$ relates magnetic field and induction as $B = \mu H$.

Curie’s Law for paramagnetic substances states that magnetic susceptibility is inversely proportional to temperature, i.e., $\chi \propto \dfrac{1}{T}$, or $\chi = \dfrac{C}{T}$, where $C$ is the Curie constant.

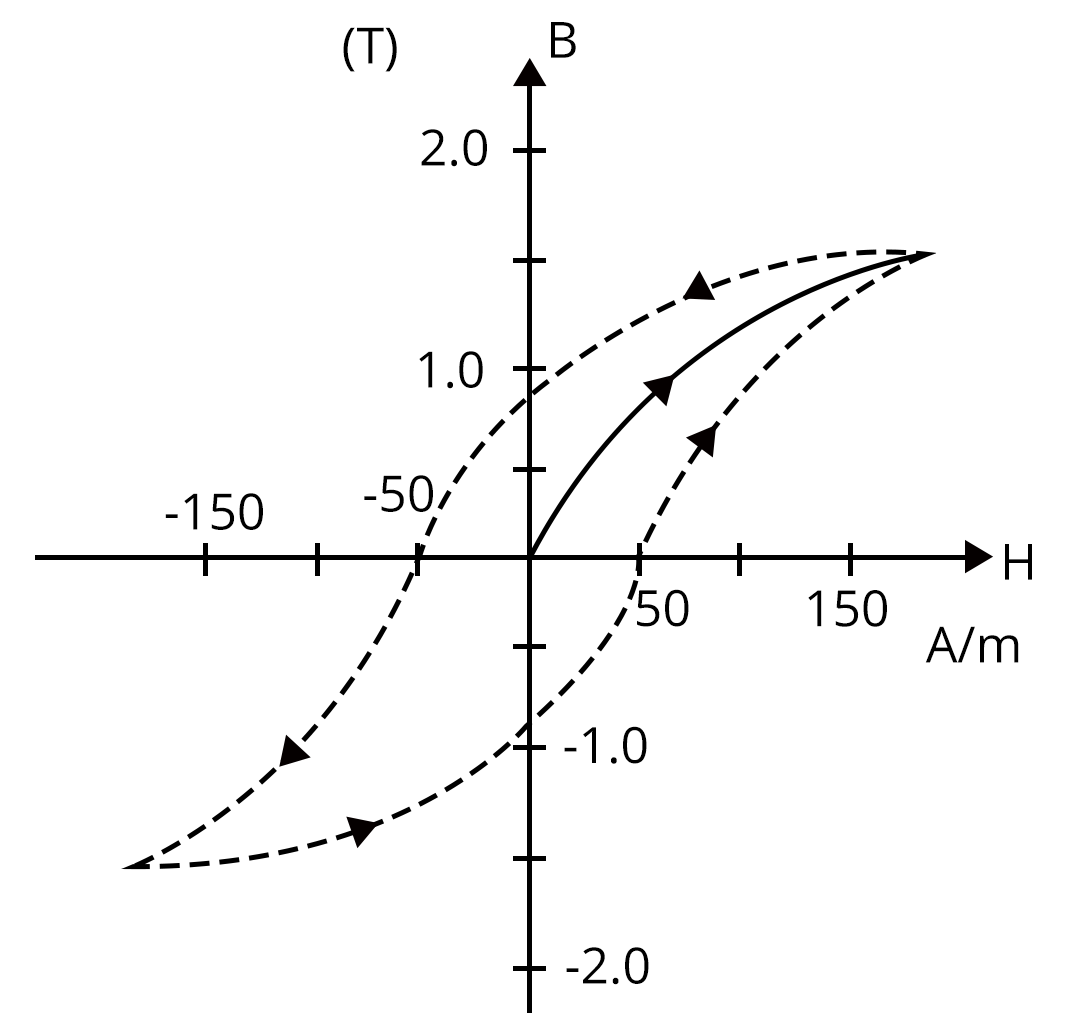

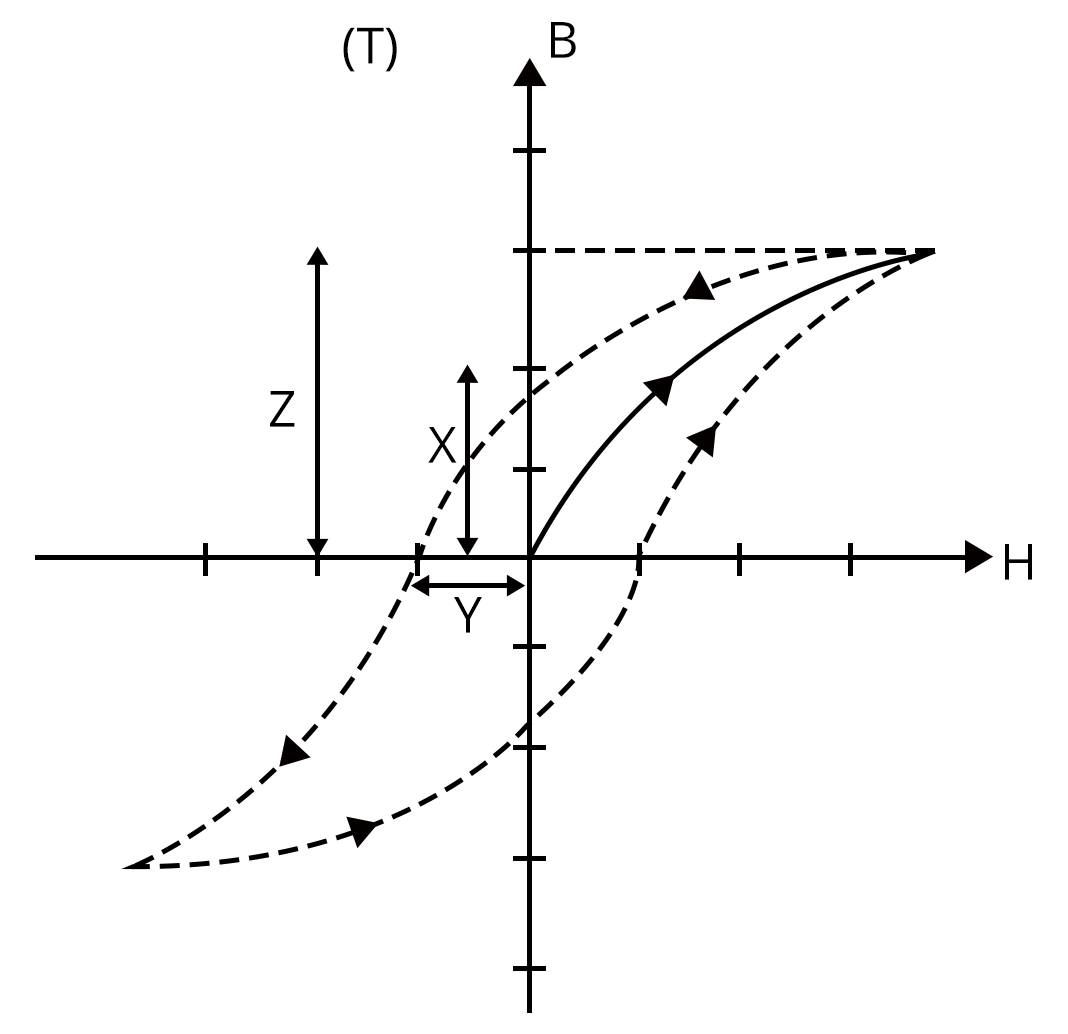

Hysteresis and Magnetic Field Lines

Hysteresis is the lag between magnetic induction $(B)$ and magnetizing field $(H)$ when a ferromagnetic material is magnetized and demagnetized. The B-H curve exhibits coercivity, retentivity, and saturation characteristics. More on this can be found at Hysteresis.

Magnetic field lines are graphical representations of the direction and strength of magnetic fields. They emerge from the north pole and enter the south pole, forming closed loops and never intersecting each other.

Sample Calculation: Magnetic Field at the Center of a Circular Coil

For a circular coil of radius $R$ with current $I$, the magnetic field at the center is $B = \dfrac{\mu_0 I}{2R}$. This formula is foundational for circular current configurations.

Key Points and Study Resources

Comprehensive study resources, including mock tests and formula sheets, are available for targeted practice. Students may access Magnetic Effects Mock Test 1 to review essential concepts for JEE Main.

- Magnetic field forms around current-carrying conductors

- Biot-Savart Law quantifies the field from small elements

- Ampere’s Law applies to symmetric situations

- Solenoids and toroids exhibit uniform internal fields

- Charged particles in a magnetic field move in circles or helices

- Materials show diamagnetic, paramagnetic, or ferromagnetic properties

FAQs on Understanding Magnetic Effects of Current and Magnetism

1. What are magnetic effects of current?

The magnetic effects of current refer to the phenomenon where an electric current flowing through a conductor produces a magnetic field around it. This fundamental concept demonstrates the connection between electricity and magnetism, and can be summarised as follows:

- When electric current flows through a wire, a magnetic field forms around the wire.

- This principle is the basis for devices like electromagnets, electric motors, and transformers.

- The direction of the magnetic field depends on the direction of current flow (as per the right-hand thumb rule).

2. State the right-hand thumb rule.

Right-hand thumb rule is a method to determine the direction of the magnetic field due to a current-carrying conductor. Summed up:

- Hold the conductor in your right hand.

- Thumb points in the direction of current.

- Fingers curl in the direction of the magnetic field lines around the conductor.

3. What is electromagnetic induction?

Electromagnetic induction is the process of generating electric current in a conductor by changing the magnetic field around it. Key points include:

- A changing magnetic field induces an electromotive force (EMF) or current in a nearby conductor.

- This phenomenon was discovered by Michael Faraday.

- It is the working principle of generators and transformers.

4. What are the applications of magnetic effects of current in daily life?

The magnetic effects of current are widely used in daily life and technology. Common applications include:

- Electric motors in fans, mixers, and appliances

- Transformers for efficient power transmission

- Electromagnets in cranes, maglev trains, and MRI machines

- Electric bells and relays

5. Explain the difference between magnetic field and magnetic field lines.

Magnetic field is the region around a magnet or current-carrying wire where a force acts on other magnetic materials or moving charges. Magnetic field lines are imaginary lines that show the direction and strength of the field.

- Field lines emerge from the north pole and enter the south pole.

- Closer lines indicate a stronger magnetic field.

- Field lines never cross each other.

6. How does a solenoid create a magnetic field?

A solenoid is a long coil of wire with many turns, and when electric current passes through it, it produces a uniform magnetic field inside. Features include:

- Magnetic field lines inside the solenoid are parallel and equally spaced, indicating a strong and uniform field.

- It acts like a bar magnet with defined north and south poles.

- The field strength increases with more current or more turns of the coil.

7. What is the principle of an electric motor?

The electric motor works on the principle that a current-carrying conductor placed in a magnetic field experiences a force. Key points:

- This force causes rotational motion in the conductor (as in the coil of a motor).

- The direction of the force is given by Fleming's Left-Hand Rule.

- Motors convert electrical energy into mechanical energy.

8. What factors affect the strength of the magnetic field produced by a current-carrying conductor?

The strength of the magnetic field around a current-carrying conductor depends on multiple factors:

- The magnitude of current (greater current = stronger field)

- The distance from the conductor (closer = stronger)

- The number of turns in a coil or solenoid

- The material inside the coil (soft iron core enhances field)

9. What are the differences between a bar magnet and an electromagnet?

Bar magnets and electromagnets both produce magnetic fields, but they differ as follows:

- Bar magnet: Permanent magnet, magnetism is always present.

- Electromagnet: Temporary, magnetism only present when current flows.

- Strength of electromagnet can be controlled; bar magnet's cannot.

- Electromagnets can have their polarity reversed by changing the current direction.

10. State and explain Fleming’s Left Hand Rule.

Fleming’s Left Hand Rule helps find the direction of force on a current-carrying conductor in a magnetic field:

- Thumb: Points in the direction of force (motion).

- Forefinger: Points in the direction of magnetic field.

- Middle finger: Points in the direction of current.

11. What is magnetic field due to a straight current-carrying conductor?

A straight current-carrying conductor produces a concentric circular magnetic field around it. Important points:

- The direction of field lines is given by the right-hand thumb rule.

- The field strength increases with more current and decreases with distance from the wire.

- Compass needle near the wire deflects, showing the presence of the field.

12. How is a current detected using a magnetic effect?

A current in a circuit can be detected using a magnetic compass or a galvanometer. Methods include:

- A compass needle placed close to a wire shows deflection when current flows, indicating a magnetic field.

- A galvanometer can measure the magnitude and direction of current based on the needle movement due to the magnetic effect.