Key Stages of Viral Infection & How Viruses Affect Living Cells

A virus is a microscopic, contagious organism that can only grow inside living cells. Virus infections are possible in all living things, including plants, animals, and microorganisms like bacteria and archaea. Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1892 publication revealing a non-bacterial pathogen infecting tobacco plants and Martinus Beijerinck's 1898 discovery of the tobacco mosaic virus, more than 9,000 virus species of the millions of types of viruses in the environment have been documented in detail. The study of viruses is known as virology, which is a subfield of microbiology. This article has explained viruses in detail. The reproduction of viruses, and how they work, all of this has been discussed in the article given below. Let’s take a look.

Virus

How Viruses Work?

Viruses are both beneficial and harmful. The Bacteriophage virus is an advantageous virus that shields people against illness by eliminating the germs that cause conditions like cholera, dysentery, typhoid, etc. Some viruses cause disease in plants or animals and are harmful. HIV, influenza virus and poliovirus are the major diseases causing disease. Viruses are transmitted by contact, by air, by food and water, and by insects, but specific types of viruses are transmitted by specific methods. Outside of the cell, viruses are dead, but once inside, their life cycle begins.

Virus Work

Reproduction of Virus

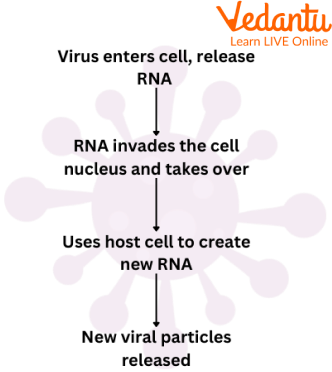

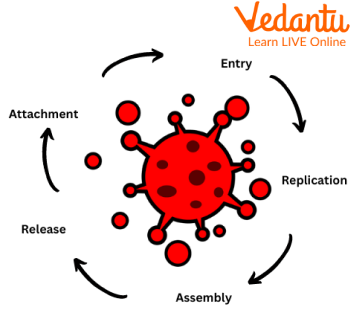

Attachment, penetration, uncoating, replication, assembly, and release are the six phases of viral replication. During attachment and penetration, the virus attaches to a host cell and injects its genetic material there. A technique known as the lytic infection is used by lytic viruses to reproduce. A virus penetrates the host cell during lytic infection, replicates, and causes the cell to lyse or explode.

Virus Reproduction

How Viruses Reproduce

The only way a virus may reproduce is if it infects a host cell. A virus is a tiny, infectious particle. In essence, viruses "command" the host cell into becoming a virus factory by using its resources to create other viruses. Because they cannot reproduce on their own, viruses are not regarded as living organisms (without a host). Viruses rely on the protein synthesis pathways of their host cell to replicate because they are unable to do so on their own. This often occurs when a virus inserts its genetic material into host cells, uses the proteins to produce viral replicas, and multiplies until the cell explodes from the high number of additional viral particles.

Viruses Reproduce

Summary

To conclude all the conceptual understanding regarding viruses in this article, we can say that every living thing has viruses, which are biological agents. While some are safe, others can spread a variety of illnesses, from the common cold to Ebola. Obtaining protection from potentially harmful viruses, such as through vaccines, can aid in the prevention of life-threatening illnesses. We have discussed enough viruses in this article. We discussed the reproduction of viruses, and how they work in the above article. We hope you enjoyed reading this article, in case of any doubts, feel free to ask in the comments.

FAQs on How Do Viruses Work? Complete Guide for Easy Understanding

1. What is a virus?

A virus is a microscopic infectious agent that is not a cell. It is made of genetic material (like DNA or RNA) enclosed in a protein coat called a capsid. Viruses are completely dependent on the living cells of other organisms, such as humans, animals, or plants, to replicate and cannot reproduce on their own.

2. What are the main parts that make up a virus?

A typical virus consists of two primary components:

Genetic Material: This is the core of the virus, which can be either DNA or RNA. It carries the instructions for making more viruses.

Capsid: A protective protein shell that encloses the genetic material. Some viruses also have an outer fatty layer called an envelope, which they acquire from the host cell.

3. How does a virus infect the body and reproduce?

A virus reproduces by hijacking a host cell in a multi-step process:

Attachment: The virus attaches itself to a specific receptor on the surface of a host cell.

Penetration: The virus or its genetic material enters the host cell.

Replication: The viral genetic material takes control of the host cell's machinery, forcing it to produce new viral components (proteins and genetic material).

Assembly: The newly made viral components assemble into complete, new viruses.

Release: The new viruses exit the host cell, often destroying it in the process, and go on to infect other cells.

4. What are the common ways viruses spread?

Viruses can spread through various methods depending on the type of virus. Common examples of transmission include:

Respiratory Droplets: Spreading through coughs and sneezes, like the influenza virus.

Direct Contact: Transmission through touch or skin-to-skin contact, such as with the virus causing warts.

Contaminated Surfaces: Touching an object with the virus on it and then touching your eyes, nose, or mouth.

Bodily Fluids: Viruses like HIV can be transmitted through the exchange of certain bodily fluids.

Contaminated Food or Water: Ingesting food or water containing viruses like Norovirus.

Insects: Bites from insects like mosquitoes can transmit viruses such as Dengue or Zika.

5. What are some examples of viruses and the diseases they cause?

There are many types of viruses that cause familiar diseases in humans. Some well-known examples include:

Rhinovirus: Causes the common cold.

Influenza virus: Causes the flu.

Varicella-zoster virus: Causes chickenpox.

Poliovirus: Causes poliomyelitis (polio).

Measles virus: Causes measles.

6. Why are viruses considered to be on the border between living and non-living things?

Viruses are often described as being on the edge of life because they exhibit characteristics of both living organisms and non-living matter.

Living traits: They possess genetic material (DNA or RNA) and can evolve through natural selection.

Non-living traits: They lack a cellular structure, have no metabolism, and cannot reproduce without a host cell. Outside a host, they are inert and can even be crystallised like a chemical salt.

7. How is a viral infection different from a bacterial infection?

While both can cause disease, viral and bacterial infections are fundamentally different. The key differences are:

Structure: Bacteria are living, single-celled organisms with all the machinery to survive on their own. Viruses are much smaller and are not cells.

Reproduction: Bacteria reproduce independently through cell division. Viruses must invade a host cell to replicate.

Treatment: Bacterial infections are treated with antibiotics, which target bacterial cells. Antibiotics have no effect on viruses. Viral infections are managed with antiviral medications that interfere with the viral life cycle.

8. Why do some viruses, like the flu virus, change every year?

Viruses change frequently because their replication process is prone to errors. When a virus rapidly copies its genetic material (DNA or RNA), small mistakes called mutations occur. Over time, these mutations can accumulate, leading to a new strain of the virus. This is why a new flu vaccine is needed each year, as the circulating strains of the influenza virus have evolved and changed from the previous year.

9. Why can't we use antibiotics to treat a viral disease like the common cold?

Antibiotics are specifically designed to kill bacteria by targeting their unique structures, such as their cell walls or metabolic pathways. Since viruses are not bacteria and lack these structures, antibiotics are completely ineffective against them. Using antibiotics for a viral infection like the common cold does not help the patient and contributes to the serious problem of antibiotic resistance in bacteria.

10. What are the main scientific theories about how viruses first originated?

Scientists have three main hypotheses to explain the origin of viruses, as they do not leave fossils:

The Progressive (or Escape) Hypothesis: Suggests viruses originated from pieces of genetic material that 'escaped' from the genes of a larger organism.

The Regressive (or Reduction) Hypothesis: Proposes that viruses were once more complex, free-living organisms that became parasitic and lost their cellular components over time.

The Virus-First Hypothesis: States that viruses evolved from complex molecules of protein and nucleic acid before or at the same time as the first cells appeared on Earth.