Key Principles and Applications of Refraction in Glass Slabs

Sir Isaac Newton agreed with Pierre Gassendi that light is made up of particles. Both perceived light as corpuscles that emanated in all directions and travelled in straight lines. The corpuscular theory explains light refraction. Therefore, investigating light will help comprehend what glass slab does to light. When it passes through the glass slab, it changes its original path and deviates.

What is Refraction of Light and Examples of Refraction of Light

The light changes its direction rather than travelling straight as it moves from one medium to another is termed as Refraction. This results in the image being either moved or deformed. The refraction of light examples are listed below:

You might see that a pencil that is partially submerged in a glass of water appears deformed.

How a spoon seems twisted or broken after being submerged in a glass of water.

How the covered letters appear shifted when a portion of the word PHYSICS is covered with a glass slab.

What is Refractive Index?

A number that indicates the speed of light in a certain medium is called its refractive index. Also, the ratio of the speed of light in a vacuum to that in a medium is represented by this dimensionless number. Assume that a given medium has a refractive index of n, speed of light in the medium v, and the speed of light in air is c. So, its refractive index is as follows by the definition:

\[{\rm{n = c/v}}\]

Laws of Refraction

When a ray enters into air from a glass slab, follow the laws of refraction listed below.

At the point of incidence, the normal ray, the incident ray, and the refracted ray to the interface of two media located on the same plane.

The ratio of the sin of the angle of incidence to that of the sin of refraction is constant or has a specific value. It is termed as Snell's law:

${{\dfrac{sin i}{sin r}} = constant = RI }$

where the constant value relies on the refractive indices of the two media used, i = angle of incidence, and r = angle of refraction.

Some Related Terms to Understand

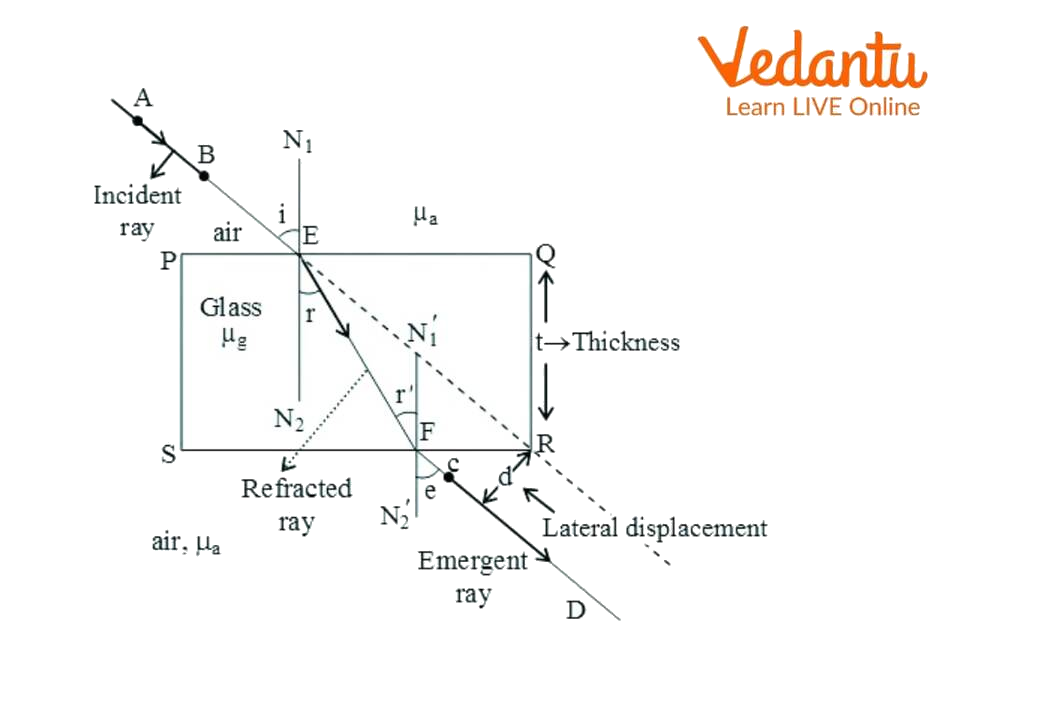

Transparent Surface: The term "transparent surface" refers to a planar surface that refracts light. The segment of a plane with a transparent surface labelled PQ in the diagram.

Point of Incidence: The point of incidence is where a light ray intersects a transparent surface. E is the point of incidence in the diagram.

Incident Rays: The incident ray is the light beam that impinges obliquely on one of the glass slab's surfaces. For observing the refraction occurring through a glass slab, we can produce incident rays from a variety of light sources. AB is the incident ray in the diagram.

Refracted Rays: A light beam is refracted by one of the surfaces that the incident light first hit. If light enters from a rarer medium into one that is denser, the refracted ray moves closer to the normal ray and if it exits from a denser medium into a rarer one, it moves farther from the normal ray. EF is the refracted ray in the diagram.

Normal Rays: We can determine the angles of incidence, refraction, and emergence by drawing two normal rays at the slab's two opposite parallel surfaces.

Emergent Rays: The emergent ray is the light ray that appears from the glass slab's other opposite face. It has been noticed or observed that the path from which the incident ray could have emerged if it had not undergone any alteration is roughly parallel to that of the emerging ray. CD is the emergent ray in the diagram.

Rectangular Glass Slab

Now let's look at the situation of what will happen when a ray of light enters from medium air to a glass slab.

Refraction Through Different Mediums

As seen in the figure above, a beam AE strikes surface PQ at an angle i. It refracts with an angle r when it enters the glass slab, bending toward normal and moving along EF. An angle of incidence of r' separates the refracted ray EF from the surface SR. When a ray enters into air from a glass slab at a refraction angle of e, the emerging ray FD deviates from the normal. As a result, although the emergent ray FD is laterally displaced with regard to the incident ray AE, it is parallel to the latter. The direction of the light changes as it leaves a parallel-faced refracting material.

Let n1 represent the refractive index of the air and n2 represent that of the glass.

According to Snell's rule,

\[{\mathop{\rm Sin}\nolimits} i/{\mathop{\rm Sin}\nolimits} r = n2/n1\]………………………………………(1) at surface P

\[{\mathop{\rm Sin}\nolimits} r/{\mathop{\rm Sin}\nolimits} e = n1/n2\]……………………………………..(2) at surface S

Since Equations (1) and (2) are reciprocals of one another, multiplying Equations (1) and (2) results into,

\[({\mathop{\rm Sin}\nolimits} i/{\mathop{\rm Sin}\nolimits} r)*({\mathop{\rm Sin}\nolimits} r/{\mathop{\rm Sin}\nolimits} e) = 1\],

Calculating further,

\[{\mathop{\rm Sin}\nolimits} i/{\mathop{\rm Sin}\nolimits} e = 1\], if i = e.

This results in the emergent ray which must be always parallel to the incident ray. Despite being parallel, the incident and emerging rays do not share the same line. This indicates that the incident ray and emerging ray have different lateral positions.

Interesting Facts

In optics and technology, refraction is used extensively. The following is a list of some of the popular applications:

Refraction allows a lens to create a picture of an object for a variety of functions, including magnification.

The concept of refraction is used in spectacles worn by those with vision problems.

Refraction is a technique used in telescopes, cameras, movie projectors, and peepholes on home doors.

Solved Problems

If the angle of incidence is 35° and the angle of refraction is 15°, what is the constant value?

Ans: \[{\mathop{\rm Sin}\nolimits} i = 35^\circ \], and \[{\mathop{\rm Sin}\nolimits} r = 15^\circ \]. We obtain the corresponding values of the provided angles from the log table.

\[{\mathop{\rm Sin}\nolimits} 35^\circ /{\mathop{\rm Sin}\nolimits} 15^\circ = 2.19\]

The 2.19 is the value of the refractive index of rays passing from one media to another.

A light beam passes through two glass slabs of the same thickness. In the first slab n1 and the second slab n2, waves form separately. Hence, what will be the refractive index of the second medium with respect to the first.

Ans: Let’s assume t, \[\lambda \], and n are the thickness of the glass slab, wavelength, and the number of waves, respectively.

\[\begin{array}{l}n*\lambda = t\\\lambda = t/n\end{array}\]

\[\lambda \alpha 1/n\] (as t is the same)

Now,

\[\lambda 1/\lambda 2 = n2*n1\]

Thus, the refractive index of the second medium w.r.t. first medium is\[{\rm{1}}\mu 2 = \lambda 1/\lambda 2 = n2/n1\]

Key Features

Due to the fact that light is moving from a rarer to a denser optical medium, the angle of refraction is smaller than the angle of incidence.

The light bends in the direction of normal when it moves from an optically rarer medium (air) to an optically denser medium (glass).

The angle of emergence and incidence are almost equal.

Conclusion

We noticed that when a ray strikes one of the parallel slab surfaces, it first experiences refraction at the surface, where it then bends toward the normal before striking the other surface that is identical to the first one. Before returning to the air through a glass slab, light experiences two refractions. The refracted light deviates from the norm the second time. The light will travel through the glass slab without deviating if it is incident at a straight angle. As we can see, the emergent ray of light emerged parallel to the incident ray preceding it. Due to its two opposed surfaces, a glass slab possesses this unique quality.

FAQs on Refraction of Light Through a Glass Slab Explained

1. What are the key phenomena observed when a light ray passes through a rectangular glass slab?

When light passes through a glass slab, two primary phenomena occur. First, the light ray undergoes refraction twice: once when entering the slab (air to glass) and again when exiting it (glass to air). Second, the emergent ray is laterally displaced but travels parallel to the original incident ray. This means it shifts sideways without changing its final direction of travel relative to the initial path.

2. What is the definition of lateral displacement in the context of a glass slab experiment?

Lateral displacement, also known as lateral shift, is the perpendicular distance between the path of the original incident ray and the path of the emergent ray after it has passed through the glass slab. This shift occurs because the light ray bends towards the normal upon entering the denser medium (glass) and away from the normal upon exiting into the rarer medium (air), resulting in a sideways shift without any deviation in the final angle.

3. How is Snell's Law applied at both surfaces of a glass slab to trace the path of light?

Snell's Law is applied at both air-glass interfaces to determine the ray's path:

- At the first surface (Air to Glass): The ray bends towards the normal. Snell's Law relates the angle of incidence (i) in air to the angle of refraction (r₁) in glass.

- At the second surface (Glass to Air): The ray bends away from the normal. As the slab's faces are parallel, the angle of incidence inside the glass (r₂) is equal to r₁. Applying Snell's Law again shows that the angle of emergence (e) becomes equal to the initial angle of incidence (i).

4. What is the formula for calculating the lateral shift, and what factors does it depend on?

The lateral displacement is determined by three main factors, and its formula illustrates this relationship. The key factors are:

- The thickness of the glass slab (t): A thicker slab causes a larger shift.

- The angle of incidence (i): A larger angle of incidence results in a greater lateral shift.

- The refractive index of the glass (n): A higher refractive index causes more bending and thus a larger shift.

5. Why does the emergent ray travel parallel to the incident ray after passing through a rectangular glass slab?

The emergent ray is parallel to the incident ray because the refraction occurs at two parallel surfaces. The extent of bending that happens when the light ray enters the glass from the air is precisely reversed when it exits the glass back into the air. Since the angle of incidence (i) at the first surface is proven to be equal to the angle of emergence (e) at the second surface, the final ray continues in the same direction as the initial ray, only shifted sideways.

6. How would the path of light change if a glass prism was used instead of a glass slab?

The primary difference is that the two refracting surfaces of a prism are not parallel, unlike a slab. Consequently, the emergent ray from a prism is not parallel to the incident ray. A prism causes deviation, bending the emergent ray at a specific angle relative to the original path. It also causes dispersion, splitting white light into its constituent colours (VIBGYOR). A glass slab, by contrast, only causes lateral displacement without changing the final direction or splitting the colours.

7. If you increase the thickness of the glass slab, what is the resulting effect on the lateral displacement?

Increasing the thickness of the glass slab directly increases the lateral displacement of the emergent ray. This is because the refracted ray must travel a longer distance within the thicker medium before it emerges. This extended path allows for a greater perpendicular (sideways) shift from its original line of travel. Therefore, a thicker slab will produce a more noticeable sideways shift of the light ray, assuming all other factors remain constant.