Raoult's Law Formula, Units & Explanation with Examples

The Raoult's Law is a key concept in JEE Main Physical Chemistry that quantitatively relates the partial vapor pressure of a component in an ideal liquid solution to its mole fraction. This principle is vital for solving problems involving vapor pressure, colligative properties, and distinguishing between ideal and non-ideal solutions. Mastery of Raoult's Law, its derivation, and real-world application can boost your JEE Chemistry performance, especially when equipped with correct formulae and stepwise explanations.

What is Raoult's Law?

Raoult's Law states: "In an ideal solution, the partial vapor pressure of each volatile component at a given temperature is directly proportional to its mole fraction in the solution." This law is crucial for understanding binary solutions and liquid mixtures in Physical Chemistry.

Raoult's Law Formula and Explanation

For a component 1 in a binary ideal solution, the law can be written as:

| Symbol | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | Partial vapor pressure of component 1 | Pa or N/m2 |

| X1 | Mole fraction of component 1 in solution | Dimensionless |

| P10 | Vapor pressure of pure component 1 | Pa or N/m2 |

The boxed formula is:

P1 = X1 · P10

Similarly, for component 2: P2 = X2 · P20

The total vapor pressure, Ptotal = P1 + P2, for a binary ideal solution.

Graphical Representation of Raoult’s Law

A plot of vapor pressure versus mole fraction in an ideal solution gives a straight-line relationship for each component and the total pressure. The individual partial pressures start at the pure component vapor pressure and decrease linearly as their mole fraction decreases. The total vapor pressure curve lies between the values for the pure components and is also linear for ideal solutions.

Stepwise Derivation of Raoult's Law

Understanding the derivation boosts conceptual clarity and scoring potential. Here is a stepwise breakdown:

- Consider a binary solution of two volatile liquids, 1 and 2, forming an ideal solution.

- On mixing, the vapor above solution contains both 1 and 2.

- The escaping tendency of each depends on its proportion at the surface, i.e., mole fraction X1 and X2.

- By the law, partial pressure of 1: P1 = X1 · P10

- Partial pressure of 2: P2 = X2 · P20

- Total vapor pressure: Ptotal = X1 · P10 + X2 · P20

- These relations hold for every composition in an ideal solution.

Applications and Examples in JEE Chemistry

Raoult’s Law is commonly tested in JEE Main through:

- Vapor pressure calculations of binary mixtures

- Questions on lowering of vapor pressure and colligative properties

- Distillation process and composition of vapor over solutions

- Determination of mole fraction in solutions from vapor pressure data

- Comparing volatility in distillation and separation techniques

Practical examples include the purification of organic solvents and design of industrial distillation columns. In JEE, you'll often calculate the composition of vapor and solution when two volatile liquids are mixed.

| Use Case | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Making Perfumes | Selecting volatile combinations for consistent scent evaporation profile using Raoult's Law |

| Fractional Distillation | Separating petroleum or alcohol-water mixtures based on vapor pressure |

| Studying Colligative Properties | Proving lowering of vapor pressure by adding non-volatile solutes |

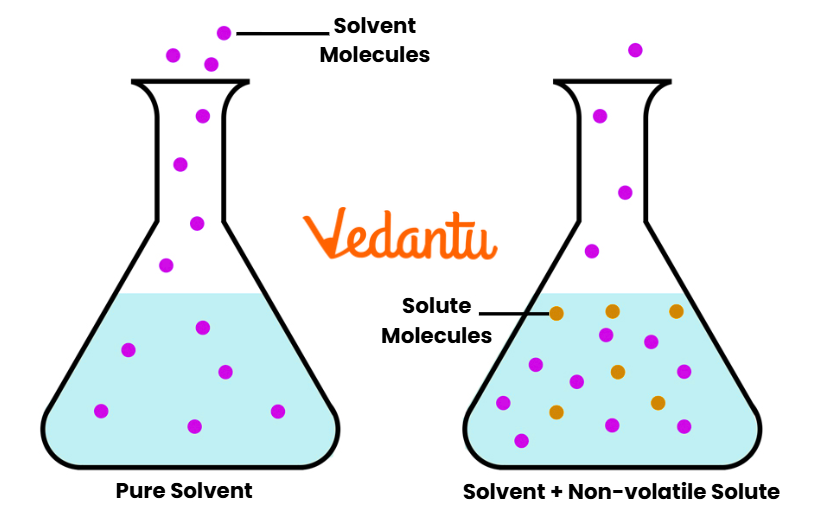

Raoult’s Law for Non-Volatile Solute

When a non-volatile solute (e.g., sugar, urea) is dissolved in a volatile solvent, the solute does not contribute to vapor pressure. Hence:

P = Xsolvent · Psolvent0

This explains the phenomenon of lowering of vapor pressure — a critical relation for colligative property problems in JEE.

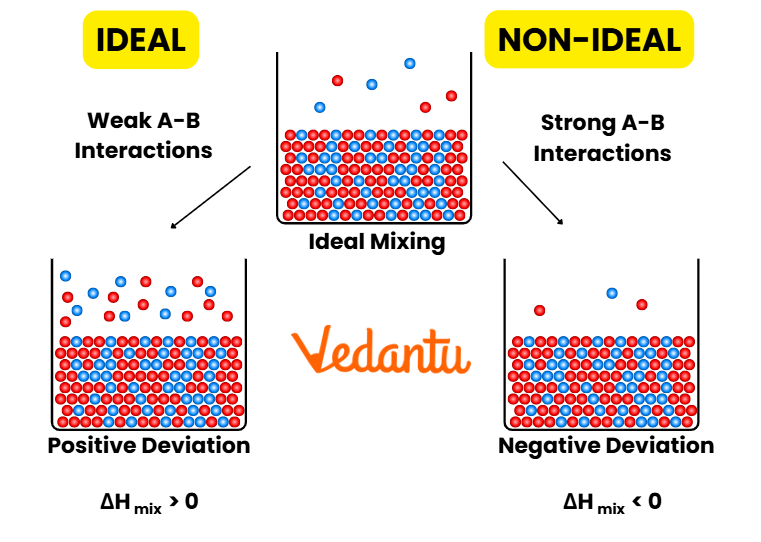

Limitations and Deviations from Raoult’s Law

Raoult’s Law strictly applies to ideal solutions, where molecular interactions between all pairs (solute-solvent and solvent-solvent) are identical. Most real solutions show positive or negative deviation due to differences in intermolecular attraction. For example, ethanol-water shows positive deviation, while acetone-chloroform shows negative deviation.

- Positive deviation: Weaker intermolecular forces than pure components. Vapor pressure higher than predicted.

- Negative deviation: Stronger intermolecular forces. Vapor pressure lower than predicted.

- Not valid for strongly interacting or associating molecules (e.g., H-bonding, electrolytes).

- Significant deviations occur near azeotropes (constant boiling mixtures).

Practice Problems: Raoult’s Law Numericals

Test your understanding with these common exam-style questions based on Raoult’s Law:

- A solution is prepared by mixing 50 g benzene (Pbenzene0 = 100.8 mmHg) and 50 g toluene (Ptoluene0 = 32.1 mmHg) at 25°C. Calculate the total vapor pressure of the solution.

- A non-volatile solute is added to 100 g water. The solution shows a vapor pressure of 22.0 mmHg at 25°C, while pure water has 23.8 mmHg at the same temperature. Find the mole fraction of solute.

- Two volatile liquids A and B are mixed. Vapor pressures at 25°C are 60 mmHg (A) and 20 mmHg (B). If XA = 0.6 and XB = 0.4, what is the total vapor pressure?

Solutions (Key Steps Only):

- Example 1: Moles benzene = 50/78, moles toluene = 50/92. Xbenzene, Xtoluene calculated, then apply Raoult’s Law and sum.

- Example 2: Xsolvent = Psolution/Ppure. Find Xsolute = 1 – Xsolvent.

- Example 3: Ptotal = XAPA0 + XBPB0 = (0.6)(60) + (0.4)(20) = 44 mmHg.

Summary Table: Raoult’s Law Cheat Sheet

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Primary Law | Raoult’s Law |

| Formula | Pi = Xi · Pi0 |

| Key Application | Vapor pressure of solutions, colligative properties |

| Valid For | Ideal solutions, dilute solutions |

| JEE Traps | For non-ideal solutions, use activity coefficients |

Further Practice and Concept Links

- Ideal and Non-Ideal Solutions – Distinguish when Raoult’s Law holds or fails.

- Solutions – Revise types, composition, and physical chemistry background.

- Distillation and Fractional Distillation – Process applications directly using Raoult's Law.

- Equilibrium – Learn about vapor phase-liquid phase coexistence.

- Solutions Practice Paper – Apply your knowledge through JEE-style questions.

- Boyle’s Law Formula – Review other gas and vapor laws linked to pressure concepts.

By mastering Raoult's Law, students build a strong foundation for solution chemistry, colligative properties, and separation techniques. For more advanced practice, check Vedantu’s JEE Main Chemistry resources, which include detailed solutions and revision materials aligned with NCERT and past exams.

FAQs on Raoult's Law Explained: Formula, Derivation, Graphs & Problems

1. What is Raoult's law in simple words?

Raoult's law states that in an ideal solution, the partial vapor pressure of each component is directly proportional to its mole fraction in the solution.

Key points:

- Applies to ideal solutions and volatile components

- Main formula: Pi = Xi × Pi°

- Essential for JEE, NEET, and board exams in Chemistry

2. What is the formula of Raoult’s Law?

The formula for Raoult’s Law expresses the relationship between partial vapor pressure and mole fraction:

- Pi = Xi × Pi°

Where:

- Pi = partial vapor pressure of component i (in the solution)

- Xi = mole fraction of component i

- Pi° = vapor pressure of pure component i

3. How does Raoult’s Law apply to non-volatile solutes?

When a non-volatile solute is added to a solvent, Raoult’s Law predicts a decrease in vapor pressure due to the solute not contributing vapor.

Key points:

- New vapor pressure: P = Xsolvent × Psolvent°

- Non-volatile solutes have Psolute° = 0

- Causes lowering of vapor pressure

- Foundation for explaining colligative properties

4. What are the limitations of Raoult’s Law?

Raoult’s Law is not valid for all solutions and has key limitations:

- Applies only to ideal solutions with similar intermolecular forces

- Fails for non-ideal solutions (e.g. strong/weak solute-solvent interactions)

- Not applicable to electrolyte solutions or associates

- Deviations occur with large size/volatility differences

5. What is Raoult's law in NCERT?

Raoult's law in NCERT Class 12 Chemistry defines it as: the partial vapor pressure of each component in an ideal solution is directly proportional to its mole fraction and equals the product of its mole fraction and vapor pressure as a pure substance.

Formula: Pi = Xi × Pi°

6. How is Raoult’s Law derived in Class 12 Chemistry?

The derivation of Raoult's Law is based on the assumption of ideal solution behavior:

- Start by considering vapor pressure of both components in pure and solution states.

- Assume molecules mix randomly and forces are similar.

- Apply Dalton’s Law of Partial Pressures for the vapor above the mixture.

- Relate partial pressure to mole fraction for each component.

7. What is Raoult's law in MCAT?

On the MCAT, Raoult's law is key to understanding solutions in chemistry:

- The partial vapor pressure of a component equals the mole fraction times its pure vapor pressure.

- Explains vapor pressure lowering when solute is added.

- Basis for colligative properties such as boiling point elevation and freezing point depression.

8. What mistakes do students make in applying Raoult’s Law in numericals?

Common errors students make in Raoult’s Law numericals include:

- Confusing mole fraction with mole percentage

- Not identifying whether the solution is ideal or non-ideal

- Incorrectly assigning vapor pressures to solute or solvents

- Forgetting to use the correct units for vapor pressure

- Applying the law to non-volatile or electrolyte solutes without modifications

9. Why do non-ideal solutions deviate from Raoult’s Law?

Non-ideal solutions deviate from Raoult’s Law due to unequal intermolecular interactions:

- Stronger or weaker forces between solute and solvent compared to pure components

- Positive deviation – weaker solute-solvent interaction, higher observed vapor pressure

- Negative deviation – stronger solute-solvent interaction, lower observed vapor pressure

- Examples: Acetone and chloroform (negative), ethanol and water (positive)

10. How does Raoult’s Law relate to colligative properties?

Raoult’s Law forms the theoretical basis for colligative properties of solutions:

- Explains lowering of vapor pressure when a non-volatile solute is added

- This leads to effects like boiling point elevation and freezing point depression

- The rationale for calculations in class 12 Chemistry

11. What is Raoult's law toppr?

On the Toppr platform, Raoult’s Law is summarized as: The partial vapor pressure of each volatile component in an ideal solution is directly proportional to its mole fraction. This concise definition helps with competitive exam revision and practice questions.