Chemistry Notes for Chapter 6 Equilibrium Class 11 - FREE PDF Download

FAQs on Equilibrium Class 11 Chemistry Chapter 6 CBSE Notes - 2025-26

1. How can I quickly summarise the concept of chemical equilibrium for revision?

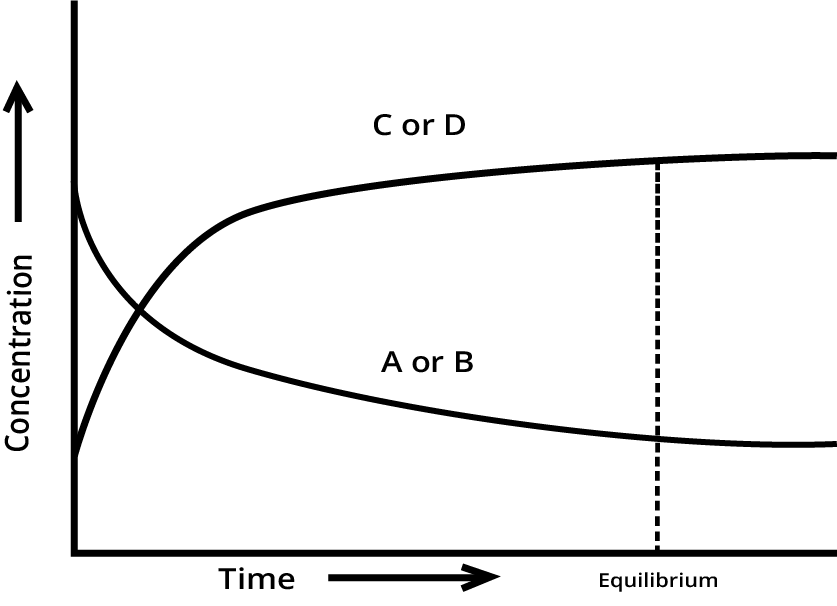

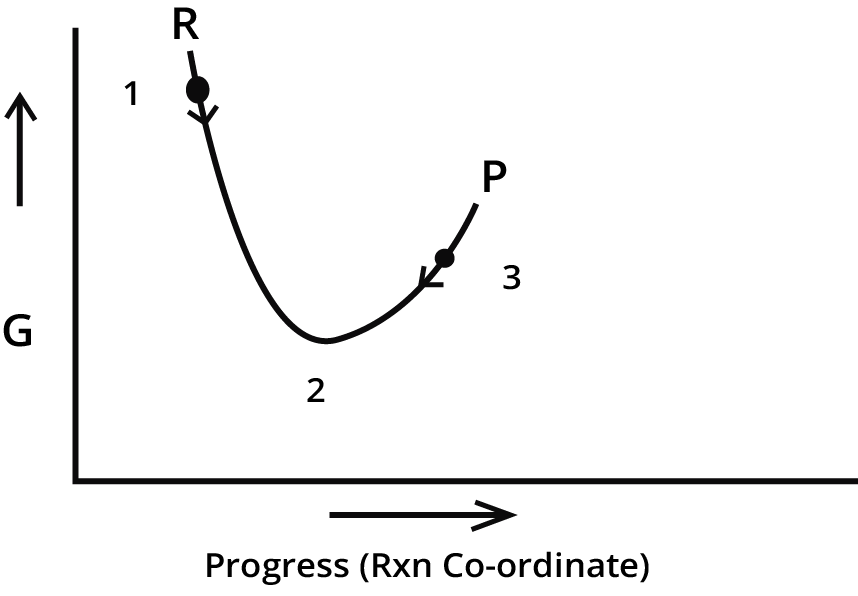

A quick summary is that chemical equilibrium is a dynamic state in a reversible reaction where the rate of the forward reaction equals the rate of the reverse reaction. This results in the concentrations of reactants and products remaining constant over time, even though the reactions are still occurring. It's a state of balance, not inactivity. For a deeper dive, you can explore the Law of Chemical Equilibrium in detail.

2. What are the essential topics to cover in a quick revision of the Class 11 Equilibrium chapter?

For an effective revision of the Equilibrium chapter, you should create a concept map covering these key areas:

Equilibrium in Physical and Chemical Processes: Understanding the basic dynamic nature.

Law of Mass Action and the Equilibrium Constant: The relationship between Kp and Kc.

Le Chatelier's Principle: How changes in concentration, temperature, and pressure affect equilibrium.

Ionic Equilibrium: Concepts of acids, bases, pH, and hydrolysis.

Buffer Solutions and Solubility Product (Ksp): Their definitions and applications.

After revising, test your knowledge with Important Questions for Class 11 Chemistry Chapter 6.

3. How does Le Chatelier's principle help in predicting the outcome of a reaction, and what's a common mistake to avoid?

Le Chatelier's principle states that if a change is applied to a system at equilibrium, the system will shift to counteract that change. This helps predict how a reaction will respond to changes in concentration, temperature, or pressure. A common mistake is thinking that adding a catalyst will shift the equilibrium. A catalyst speeds up both the forward and reverse reactions equally, allowing equilibrium to be reached faster, but it does not change the position of the equilibrium itself.

4. Why are there two different equilibrium constants, Kp and Kc, and how do I decide which to use in a summary?

The two constants exist to handle different states of matter. Kc uses the molar concentrations of reactants and products, making it suitable for aqueous solutions and gases. Kp uses the partial pressures of gaseous reactants and products, so it is used exclusively for reactions involving gases. For a quick summary, remember: if the reaction involves gases and pressure data is given, use Kp. Otherwise, or for solutions, use Kc. They are related by the formula Kp = Kc(RT)Δng.

5. What is the core difference to remember between physical and chemical equilibrium for a quick recap?

The core difference is in the substances involved. Physical equilibrium is a balance between different phases of the same substance, such as ice melting into water (H₂O(s) ⇌ H₂O(l)). Chemical equilibrium, however, is a balance in a reversible reaction where reactants form new chemical substances (products), such as the formation of ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen (N₂(g) + 3H₂(g) ⇌ 2NH₃(g)).

6. Can you provide a concise summary of ionic equilibrium for Class 11?

Ionic equilibrium is the part of the chapter that deals with the balance of ions in a solution, mainly in water. The key concepts to summarise are:

Acids and Bases: Definitions according to Arrhenius, Brønsted-Lowry, and Lewis theories.

Ionization: The extent to which strong and weak electrolytes dissociate into ions.

pH Scale: A measure of acidity or alkalinity in a solution.

Salt Hydrolysis: How salts of weak acids or bases react with water to change the solution's pH.

For practice, you can refer to the NCERT Solutions for Class 11 Equilibrium.

7. Beyond definitions, how do buffer solutions and the common ion effect practically work to resist pH changes?

Practically, a buffer solution (a weak acid and its conjugate base, or a weak base and its conjugate acid) resists pH change by having a component to neutralize added acid and another to neutralize added base. The common ion effect is the underlying mechanism. When an ion common to the weak electrolyte is added, it suppresses the electrolyte's ionization, shifting the equilibrium. In a buffer, this effect keeps the concentrations of the acid/base and its conjugate partner stable, ready to absorb pH shocks.

8. What is the key takeaway about the solubility product (Ksp) for revision purposes?

The key takeaway is that the Solubility Product (Ksp) is an equilibrium constant that quantifies the solubility of a sparingly soluble salt. For a salt like AgCl, Ksp = [Ag⁺][Cl⁻]. A higher Ksp value means the salt is more soluble. It is crucial for predicting whether a precipitate will form when two solutions are mixed: if the ionic product (Qsp) exceeds the Ksp, precipitation occurs.