Key Differences Between Solids and Liquids for Students

The study of the properties of solids and liquids in physics focuses on understanding the mechanical and thermal behavior of matter in these two states. This includes elasticity, stress-strain relationships, fluid statics and dynamics, surface phenomena, viscosity, and heat transfer processes. Mastering these concepts is fundamental for solving a wide range of problems in both engineering and the physical sciences, and is particularly important for JEE Main exam preparation.

Elasticity and Stress-Strain Relations in Solids

Elasticity refers to the ability of a solid to return to its original shape and size after the removal of a deforming force. Solids respond to external forces with stress, which is the restoring force per unit area, and strain, defined as the ratio of change in dimension to the original dimension.

Stress is given by $ \text{stress} = \dfrac{\text{Force}}{\text{Area}} $. Its SI unit is N/m$^2$. Strain is a dimensionless quantity, such as longitudinal strain $ = \dfrac{\Delta l}{l} $ or volume strain $ = \dfrac{\Delta V}{V} $.

Different types of stress include longitudinal (normal), shearing (tangential), and volume (bulk) stress. These lead to corresponding strains, and the ratio between stress and strain under specific conditions defines material modulus of elasticity.

Modulus of Elasticity: Young’s, Bulk, and Rigidity Modulus

Young’s modulus ($Y$) is the ratio of longitudinal stress to longitudinal strain. It describes the extent to which a material will stretch or compress under linear force. The formula is $Y = \dfrac{F/A}{\Delta l / l} = \dfrac{Fl}{A \Delta l}$.

Bulk modulus ($B$) expresses how a material responds to uniform pressure, defined as $B = -\dfrac{\Delta P}{\Delta V / V}$. The negative sign indicates that an increase in pressure causes a decrease in volume. This modulus applies to solids, liquids, and gases.

Modulus of rigidity ($\eta$) is the ratio of shearing stress to shearing strain: $ \eta = \dfrac{F/A}{x/h} $, where $x$ is the displacement and $h$ is the height.

Hooke’s Law and the Stress-Strain Curve

Hooke’s Law states that, within the elastic limit, stress is directly proportional to strain $(\sigma = Y \varepsilon)$. The proportionality constant is the modulus of elasticity. Materials generally obey Hooke’s Law up to the proportional limit, beyond which plastic deformation occurs.

A stress-strain curve visually represents how a material deforms under increasing load. Key points include the proportional limit, yield point, ultimate strength, and breaking point. Ductile materials exhibit significant plastic deformation before failure, while brittle materials break soon after the elastic limit.

Potential Energy in a Stretched Wire

When a wire is stretched by a force, the work done is stored as elastic potential energy. The energy stored per unit volume is $ U_v = \dfrac{1}{2} \text{stress} \times \text{strain} $ or $ U_v = \dfrac{1}{2} Y (\text{strain})^2 $.

Mechanical Properties of Liquids: Pressure and Pascal’s Law

Liquids can flow and take the shape of their container. The pressure at a depth $h$ in a static liquid column is $ P = \rho g h $, where $\rho$ is the fluid density and $g$ is the acceleration due to gravity. Pressure increases linearly with depth.

According to Pascal’s Law, a change in pressure applied to an enclosed incompressible fluid is transmitted undiminished to all parts of the fluid. This principle is utilized in hydraulic machines and braking systems.

Archimedes’ Principle and Buoyancy

Archimedes’ Principle states that any object fully or partially immersed in a fluid experiences an upward buoyant force equal to the weight of the displaced fluid. The buoyant force is calculated by $F_B = \rho_{\ell} V g$, where $V$ is the submerged volume. This concept explains flotation and sinking.

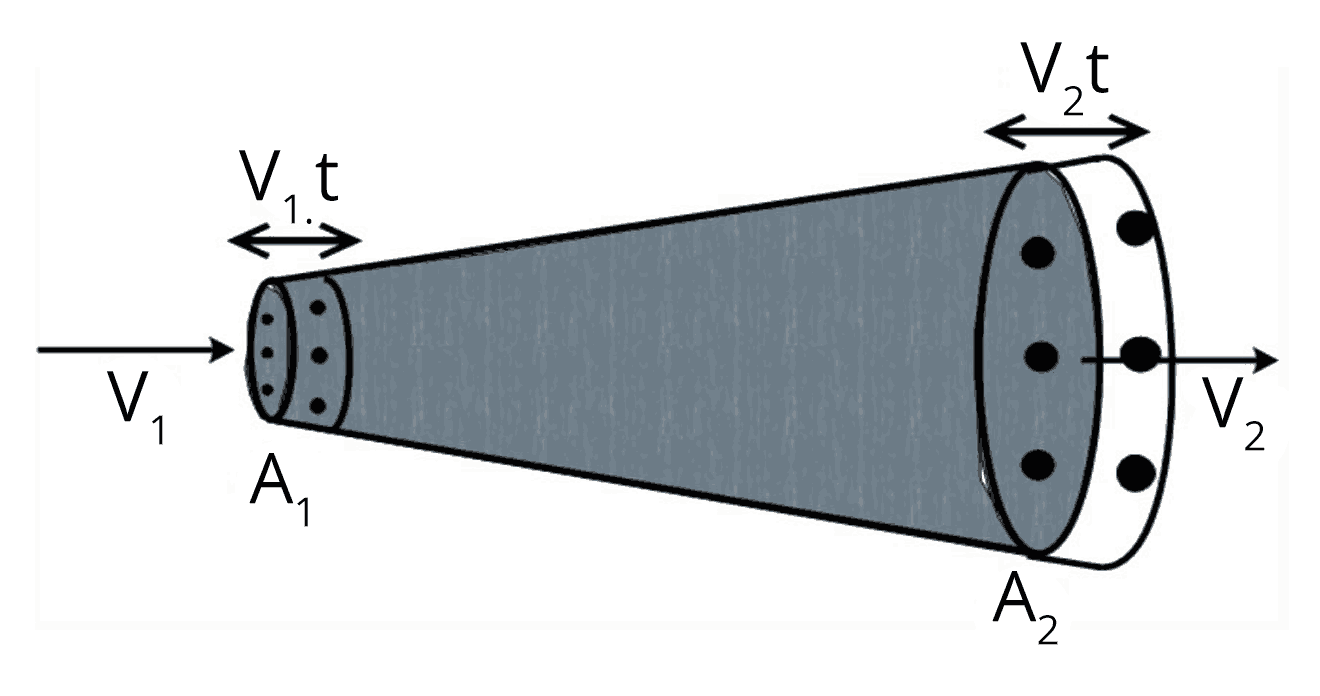

Bernoulli’s Theorem and Fluid Dynamics

Bernoulli’s theorem states that, for an incompressible and non-viscous fluid in steady flow, the sum of pressure energy, potential energy, and kinetic energy per unit volume is constant along a streamline.

The equation is $ P + \rho g h + \dfrac{1}{2} \rho v^2 = \text{constant} $. This relation is fundamental for understanding fluid motion, including lift generation and fluid jets. For targeted practice, see Properties Of Solids And Liquids Mock Test 1.

Viscosity and Stoke’s Law

Viscosity is the property of a fluid that resists relative motion between its layers. The viscous force for a sphere of radius $r$ moving with velocity $v$ in a fluid with viscosity $\eta$ is given by Stoke’s Law: $F = 6 \pi \eta r v$.

Terminal velocity is the constant speed attained by a body falling through a viscous fluid when downward force balances viscous drag and buoyancy. Reynolds number is used to predict whether the fluid flow is laminar or turbulent.

Surface Tension and Surface Energy

Surface tension arises due to cohesive forces between liquid molecules at the surface, acting to minimize surface area. The unit of surface tension is N/m. Surface energy is potential energy present at the surface due to molecular interactions, numerically equal to surface tension.

The mathematical relationship is $ \text{Surface tension} = \dfrac{\text{Surface energy}}{\text{Area}} $. This concept has practical applications, such as the shape of droplets and capillary rise. Additional explanations are available at Properties Of Solids And Liquids Practice Paper.

Angle of Contact and Capillarity

The angle of contact between a liquid and a solid surface determines the shape of the liquid meniscus. Capillary action occurs due to surface tension when a liquid rises or falls in a narrow tube. The height of capillary rise is $ h = \dfrac{2S \cos \theta}{\rho r g} $.

Heat, Temperature, and Thermal Expansion

Heat represents the transfer of thermal energy, while temperature measures the average kinetic energy of particles. Thermal expansion describes how substances change their dimensions with temperature. For solids, linear expansion is $ \Delta L = L_0 \alpha \Delta T $; for liquids, volume expansion is observed.

Specific Heat, Calorimetry, and Latent Heat

Specific heat capacity is the heat required to raise the temperature of a unit mass by one degree. Calorimetry involves quantitative measurement of heat exchange. During phase changes, the absorbed or released energy is called latent heat, calculated as $ Q = m L $, where $L$ is latent heat constant.

Modes of Heat Transfer: Conduction, Convection, and Radiation

Heat transfer occurs via conduction (direct molecular interaction, mainly in solids), convection (movement of fluids), and radiation (electromagnetic waves). The rate of heat transfer by conduction through a slab is $ \dfrac{Q}{t} = \dfrac{KA\, \Delta T}{L} $.

Black Body Radiation and Stefan-Boltzmann Law

A black body absorbs all incident radiation and emits maximum possible energy at a given temperature. According to Stefan-Boltzmann law, radiant energy emitted per unit area per unit time is proportional to the fourth power of absolute temperature: $ E = \sigma T^4 $.

Wien’s Displacement Law and Newton’s Law of Cooling

Wien’s law states that the wavelength at maximum emission is inversely proportional to temperature: $ \lambda_m T = b $, where $b$ is a constant. Newton’s Law of Cooling asserts that for a small temperature difference, the rate of cooling is proportional to the temperature difference between the body and surroundings.

Sample Problems and Key Formulas

Calculation of stress, energy stored in stretched wires, capillary rise, buoyant force, and pressure differences are common problems in this topic. Essential formulas and worked examples reinforce conceptual clarity for exam preparation. For more advanced practice, review Properties Of Solids And Liquids Important Questions.

| Concept | Key Formula |

|---|---|

| Young’s Modulus | $Y = \dfrac{Fl}{A \Delta l}$ |

| Bulk Modulus | $B = -\dfrac{\Delta P}{\Delta V / V}$ |

| Stoke’s Law | $F = 6\pi \eta r v$ |

| Stefan-Boltzmann Law | $E = \sigma T^4$ |

| Capillary Rise | $h = \dfrac{2S \cos \theta}{\rho r g}$ |

Applications and Additional Resources

The concepts in this chapter are foundational for understanding a range of natural and engineered phenomena, including structural design, fluid flow, and heat management. For revision notes, visit the Properties Of Solids And Liquids Revision Notes.

For focused study on solids, students can refer to the supplementary material at Properties Of Solids.

Understanding the Properties of Solids and Liquids

Share

Share

Watch Video

Watch Video