How is Angular Momentum Calculated for a Rotating Object?

Angular momentum of a rotating body is a key concept in rotational dynamics, quantifying the rotational motion possessed by an object about a given axis. In physics, it provides a measure of how difficult it is to change the rotational state of a body. Understanding its definition, mathematical expression, direction, and conservation is important for analyzing problems in rotational motion at the JEE level.

Linear Momentum and its Significance

Linear momentum refers to the quantity of motion an object possesses due to its velocity and mass. It is given by $p = mv$, where $m$ is the mass and $v$ is the velocity of the object. The SI unit of momentum is $\mathrm{kg\,m\,s^{-1}}$. Linear momentum is always associated with objects in translational motion.

In rotational dynamics, the concept of momentum is extended to angular momentum, which applies when objects rotate about a fixed axis. Angular momentum plays an analogous role in rotational motion as linear momentum does in translational motion.

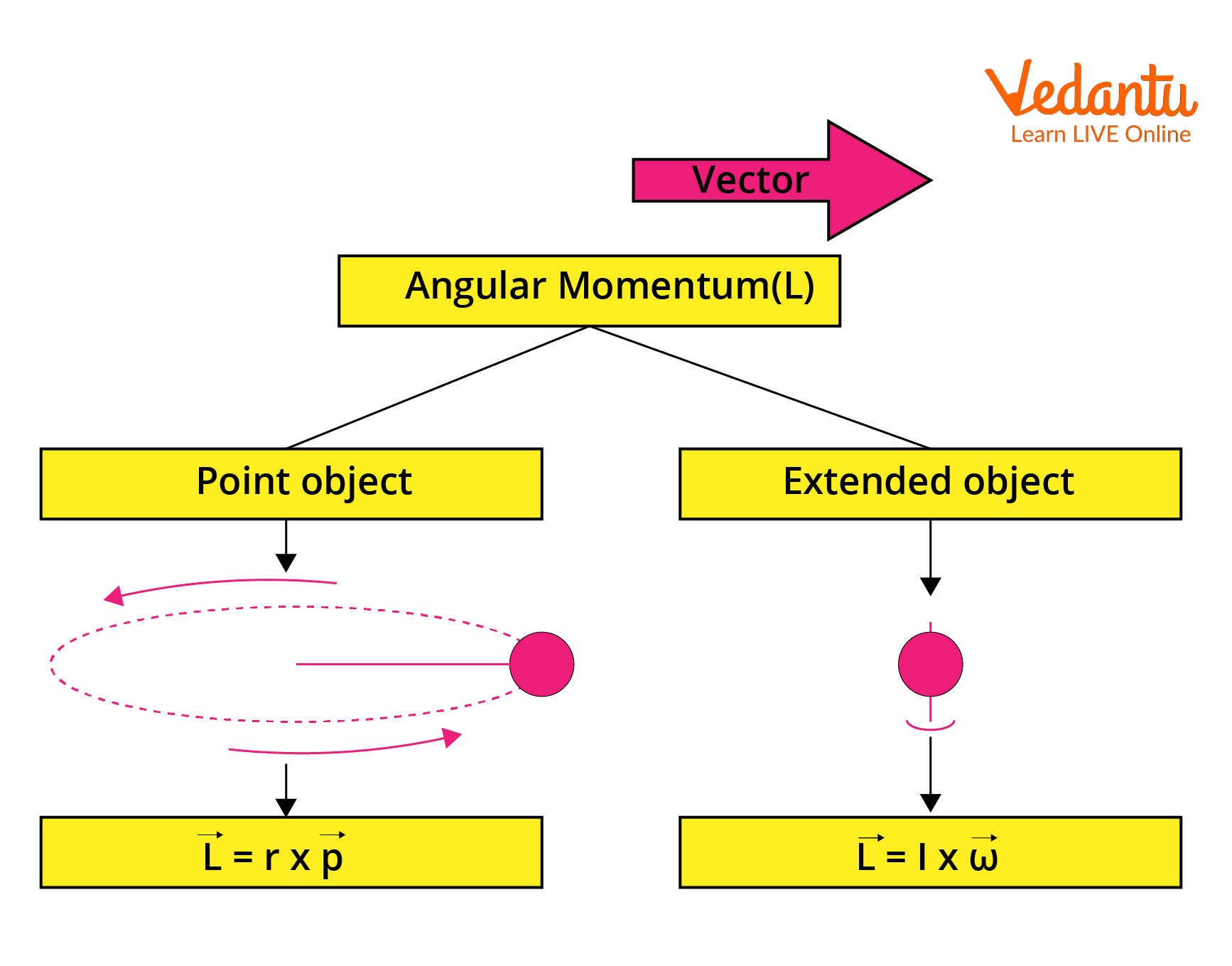

Defining Angular Momentum

Angular momentum is a physical quantity that describes the rotational motion of an object about an axis. For a point mass moving in a plane, angular momentum is defined as the cross product of the position vector ($\vec{r}$) and its linear momentum ($\vec{p}$):

$\vec{L} = \vec{r} \times \vec{p}$

Here, $\vec{L}$ is the angular momentum vector, $\vec{r}$ is the position vector from the axis of rotation to the particle, and $\vec{p}$ is the linear momentum. The direction of angular momentum follows the right-hand rule.

For further details on forces in rotational dynamics, refer to Torque.

Angular Momentum of an Extended or Rigid Body

For an extended rigid body rotating about a fixed axis, the angular momentum is calculated as the product of its moment of inertia ($I$) and angular velocity ($\omega$):

$L = I\omega$

Here, $I$ denotes the moment of inertia about the axis of rotation, and $\omega$ is the angular velocity. The moment of inertia represents the distribution of mass relative to the rotation axis, affecting the rotational motion of the body.

The mathematical derivation for a rigid body composed of $N$ particles of masses $m_1, m_2, ..., m_N$ at perpendicular distances $r_1, r_2, ..., r_N$ from the axis gives:

$\displaystyle L = \sum_{i=1}^{N} m_i r_i^2 \omega = I\omega$

This relation holds when the body performs pure rotational motion about a fixed axis. For details on how mass distribution influences $I$, see Moment of Inertia.

Direction and Vector Nature of Angular Momentum

Angular momentum is a vector quantity with both magnitude and direction. The direction of $\vec{L}$ is perpendicular to the plane formed by $\vec{r}$ and $\vec{p}$, following the right-hand rule. For a rigid rotating body, its direction coincides with the axis of rotation following the same rule.

In vector notation for a rigid body, angular momentum can be expressed as $\vec{L} = I\vec{\omega}$, where $\vec{\omega}$ is the angular velocity vector.

Conservation of Angular Momentum

The law of conservation of angular momentum states that if no external torque acts on a system, its total angular momentum remains constant. This principle is mathematically represented as:

$\dfrac{d\vec{L}}{dt} = \vec{\tau}_{\text{ext}}$

When $\vec{\tau}_{\text{ext}} = 0$, then $\vec{L}$ is conserved. Conservation of angular momentum is fundamental in rotational motion and plays a crucial role in various physical scenarios and problem solving in Rotational Motion.

Key Equations for Angular Momentum of Rotating Bodies

| Expression | Description |

|---|---|

| $\vec{L} = \vec{r} \times \vec{p}$ | Angular momentum of a point mass |

| $L = I\omega$ | For a rotating rigid body |

| $I = \sum m_i r_i^2$ | Moment of inertia for discrete masses |

| $\vec{\tau} = \dfrac{d\vec{L}}{dt}$ | Relation with external torque |

Typical Changes in Angular Momentum

If the moment of inertia is altered while conserving angular momentum, any change in $I$ is compensated by a change in $\omega$. For example, if the moment of inertia of a rotating body decreases by $20\%$ and no external torque acts, the angular velocity increases to conserve $L$.

- Decrease in $I$ increases $\omega$ for constant $L$

- Increase in $I$ decreases $\omega$ for constant $L$

If the angular momentum increases by a specific percentage, such as $20\%$ or $200\%$, this affects the rotational kinematics and must be calculated according to $L=I\omega$.

Solved Example: Angular Momentum of a Rotating Disc

Consider a disc of mass $M = 2\,\mathrm{kg}$ and radius $R = 0.5\,\mathrm{m}$ rotating at angular velocity $\omega = 10\,\mathrm{rad/s}$. The moment of inertia about its axis is $I = \dfrac{1}{2}MR^2$. The angular momentum is:

$I = \dfrac{1}{2} \times 2 \times (0.5)^2 = 0.25\,\mathrm{kg\,m^2}$

$L = I\omega = 0.25 \times 10 = 2.5\,\mathrm{kg\,m^2\,s^{-1}}$

Important Points Regarding Angular Momentum

- Angular momentum is conserved if external torque is zero

- $L = I\omega$ applies for pure rotation about a fixed axis

- Direction determined by right-hand rule

- SI unit is $\mathrm{kg\,m^2\,s^{-1}}$

Comparing angular momentum with other physical quantities enhances understanding. For distinctions with linear motion concepts, see Difference Between Work and Energy.

Frequently Asked Questions: Angular Momentum of Rotating Body

Q1: Is angular momentum always conserved in a rotating system?

Angular momentum is conserved only in the absence of external torque. If external torques act, the angular momentum of the system changes at a rate equal to the net external torque applied.

Q2: What is the effect on angular velocity if the moment of inertia of a rotating body is increased in the absence of external torque?

If the moment of inertia increases and no external torque is present, the angular velocity decreases such that the product $I\omega$ remains constant, preserving angular momentum.

For foundational understanding of motion, consult the section on Kinematics.

FAQs on Understanding Angular Momentum in Rotating Bodies

1. What is angular momentum of a rotating body?

Angular momentum of a rotating body is a physical quantity that measures the rotational motion of the object around a fixed axis. It is calculated as the product of the body's moment of inertia and its angular velocity.

- Mathematically, L = I × ω, where L is angular momentum, I is moment of inertia, and ω is angular velocity.

- It is a vector quantity and follows the right-hand rule.

- Angular momentum is conserved in the absence of external torque.

2. State the law of conservation of angular momentum.

The law of conservation of angular momentum states that if no external torque acts on a system, the total angular momentum of the system remains constant.

- This means: Initial angular momentum = Final angular momentum

- Expressed as: I1ω1 = I2ω2

- This law is widely used in physics to explain phenomena such as a spinning figure skater pulling in their arms to spin faster.

3. How is angular momentum different from linear momentum?

Angular momentum relates to rotational motion, while linear momentum is associated with straight-line movement. Key differences include:

- Angular momentum (L): Product of moment of inertia and angular velocity.

- Linear momentum (p): Product of mass and linear velocity.

- Angular momentum is a rotational counterpart of linear momentum.

- Both are conserved, but their conservation applies to different physical situations.

4. What is the SI unit of angular momentum?

The SI unit of angular momentum is kg·m2/s (kilogram meter squared per second).

- It can also be expressed as Newton-meter-second (N·m·s).

5. Derive the expression for angular momentum of a rotating rigid body.

The angular momentum (L) of a rotating rigid body is derived as follows:

- Consider a rigid body rotating with angular velocity ω.

- The moment of inertia is I about the axis.

- Thus, L = I × ω, where:

- L: Angular momentum

- I: Moment of inertia (depends on mass distribution)

- ω: Angular velocity

6. What factors affect the angular momentum of a rotating body?

The angular momentum of a rotating body depends on two main factors:

- Moment of inertia (I): Depends on the mass and how it is distributed relative to the axis of rotation.

- Angular velocity (ω): The speed at which the body rotates.

- Both greater mass further from the axis and higher rotational speed increase angular momentum.

7. Give an example showing conservation of angular momentum in daily life.

A common example of conservation of angular momentum is a figure skater spinning.

- When the skater pulls in their arms, their moment of inertia decreases.

- Since no external torque acts, their angular velocity increases to conserve angular momentum.

- Similarly, a rotating chair speeds up if you pull your legs closer to the axis.

8. How is angular momentum conserved in planetary motion?

In planetary motion, the angular momentum of a planet about the sun remains constant, provided no external torque acts.

- As a planet moves closer to the sun in its orbit, its velocity increases.

- When the planet is farther, its velocity decreases.

- This inverse relationship keeps L = mvr constant and is demonstrated by Kepler’s second law.

9. What is moment of inertia and how does it relate to angular momentum?

The moment of inertia measures how the mass of a body is distributed about a rotational axis and determines the resistance to change in rotational motion.

- It is directly proportional to angular momentum (L = I × ω).

- A higher moment of inertia means greater angular momentum for a given angular velocity.

10. Can angular momentum be negative? Explain.

Yes, angular momentum can be negative, depending on the direction of angular velocity relative to the chosen reference axis.

- If the rotation is in the opposite direction to the positive axis (as defined), the angular momentum is considered negative.

- This convention helps describe clockwise and counterclockwise rotational motions.