Key Characteristics and Differences Among the Five Kingdoms Explained

The Five Kingdoms Classification is a system in biology used to arrange all living organisms based on their evolutionary relationships and cellular makeup. This approach separates life forms into five broad kingdoms: Monera, Protista, Fungi, Plantae, and Animalia. Developed for clarity, this method helps students, researchers, and educators better understand biodiversity, evolution, and organism structure for various biological applications.

What is Five Kingdoms Classification?

Five kingdoms classification is a scientific method to organize living things into five major groups. This model, proposed by R.H. Whittaker in 1969, relies on criteria such as cell type, body organization, nutrition, reproduction modes, and evolutionary history. The primary aim is to categorize organisms more accurately than older two- or three-kingdom systems, offering a clearer picture of life’s diversity, structure, and functions.

A Brief History of Classification Systems

Early biologists grouped living organisms as either plants or animals, but advances in microscopy revealed more complexity. The discovery of microorganisms and the differences between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells highlighted the limitations of the two-kingdom system. Over time, contributions by scientists like Haeckel, Copeland, and Whittaker refined organism classification, leading to the five kingdoms classification system now widely used in textbooks and competitive exams.

Basis of Five Kingdoms Classification

Whittaker’s classification considers several fundamental characteristics to place organisms in their respective kingdoms:

- Cell Structure: Is the organism prokaryotic (no nucleus) or eukaryotic (with a nucleus)?

- Body Organization: Unicellular or multicellular body plan.

- Mode of Nutrition: Organisms may be autotrophic (self-feeding by photosynthesis) or heterotrophic (feeding on others).

- Reproduction: Methods can be asexual (like binary fission) or sexual (gamete fusion).

- Phylogenetic Relationships: Evolutionary lineage based on genetics and morphology.

The Five Kingdoms: Definition and Characteristics

1. Kingdom Monera

Monera includes all prokaryotic organisms, such as bacteria and cyanobacteria (blue-green algae). These unicellular life forms lack a nucleus and membrane-bound organelles. Monerans thrive in diverse habitats, from soil and water to extreme environments. Reproduction is mainly asexual, typically by binary fission. Nutrition methods vary—some are autotrophs and others are heterotrophs.

- Unicellular, prokaryotic

- No true nucleus or organelles

- Some cause diseases; others help in food production and nitrogen fixation

- Examples: Escherichia coli, Streptococcus, cyanobacteria

To learn more about bacteria, visit What is Bacteria?

2. Kingdom Protista

Protista comprises mainly unicellular eukaryotic organisms. Most live in aquatic environments and can be plant-like (algae), animal-like (protozoa), or fungus-like (slime molds). Their modes of nutrition and reproduction are very diverse. Some protists, like Plasmodium, are known to infect humans or animals.

- Unicellular, eukaryotic

- Both autotrophic and heterotrophic nutrition

- Sexual and asexual reproduction

- Examples: Amoeba, Paramecium, Euglena, Diatoms, Plasmodium

3. Kingdom Fungi

Fungi are mostly multicellular eukaryotes known for their unique nutrition—they absorb nutrients from decaying organic matter. Fungal cell walls contain chitin, distinguishing them from plants. Fungi are essential decomposers, but some cause diseases like powdery mildew. Important examples include yeast, molds, and mushrooms.

- Multicellular (except yeast), eukaryotic

- Cell walls made of chitin

- Reproduction by spores, with both sexual and asexual types

- Examples: Agaricus (mushroom), Rhizopus (bread mold), Saccharomyces (yeast)

Explore more about fungal infections at Powdery Mildew.

4. Kingdom Plantae

Plantae is the kingdom of all multicellular, eukaryotic organisms that can perform photosynthesis. Their cell walls are made of cellulose. This kingdom ranges from simple algae to complex flowering plants. Plants play a vital role in oxygen production and human nutrition.

- Multicellular, eukaryotic, photosynthetic

- Cellulose cell walls

- Complex life cycles (alternation of generations)

- Examples: Mosses, Ferns, Pines, Mango tree (Mangifera indica)

For further reading, try Adaptations in Plants or Tree Leaves.

5. Kingdom Animalia

Animalia includes all multicellular, eukaryotic, heterotrophic organisms. Animals lack cell walls and obtain food by ingestion. Members store energy as glycogen or fat, and most show complex movement and nervous systems.

- Multicellular, eukaryotic, heterotrophic

- Lack cell walls

- Reproduction mainly sexual

- Examples: Insects, fish, birds, humans

Read about animal adaptations at Animal Adaptations and Animal Kingdom Classification.

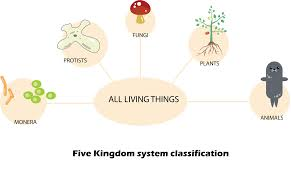

Five Kingdoms Classification Diagram

The diagram above summarises the diverse characteristics that set each kingdom apart, such as the presence of a nucleus, cell wall composition, and modes of nutrition. Such visual aids help students quickly compare key differences for exams and assignments.

Five Kingdoms Classification Examples

- Monera: Streptococcus, Nostoc, Spirillum

- Protista: Paramecium, Chlamydomonas, Amoeba

- Fungi: Penicillium, Aspergillus, Yeast

- Plantae: Rose, Rice, Mango tree, Ferns

- Animalia: Earthworm, Butterfly, Lion, Human (Homo sapiens)

These examples show the wide range of organisms grouped under each kingdom, creating a solid foundation for understanding topics like food chains, evolution, and nutrition.

Merits and Demerits of Five Kingdoms Classification

Merits

- Makes distinction between prokaryotes (Monera) and eukaryotes (all other kingdoms).

- Separates unicellular (Monera, Protista) from multicellular organisms (Fungi, Plantae, Animalia).

- Keeps fungi apart from plants based on nutrition and structure (see Algae vs Fungi).

- Highlights evolutionary relationships based on cellular organization and gene sequencing.

Demerits

- Viruses are not included, as they do not fit into any kingdom due to their unique structure (learn more at Virus).

- Some similar organisms are placed apart, such as unicellular and multicellular algae.

- Diverse organisms like Archaebacteria and Eubacteria are placed together in Monera, despite significant differences.

- Symbiotic organisms like lichens are not properly classified.

Five Kingdoms Classification in Modern Biology

The five kingdoms system supports studies in medicine, agriculture, food, and environmental science. For example, bacterial classification helps in Food Science and nutrition. In environmental studies, plant and fungal diversity relate to topics like climate change and ecosystem management. Vedantu offers in-depth resources for students aiming to master the five kingdoms classification for exams and projects.

Five Kingdoms Classification: MCQs and Questions

Studying the five kingdoms classification prepares students for competitive exams and class 12 board questions. MCQs may test you on characteristics, examples, and the basis of classification. Practising such questions sharpens understanding of key biological terms and processes. For further practice, visit important biology diagrams and MCQs on reproduction.

Five Kingdoms Classification PPT and Projects

For projects and presentations, use diagrams, tables, and real-world examples to explain the five kingdoms classification. Highlight differences between kingdoms, representative species, and their roles in nature and industry. Refer to Vedantu’s Biology Projects for Class 11 for inspiration.

Comparison with Other Classification Systems

Unlike older two- or three-kingdom systems, the five kingdoms approach offers a more accurate representation of evolutionary relationships. Recent molecular studies have led to further refinements, such as distinguishing Archaea from Bacteria. However, five kingdoms classification remains a fundamental concept in school and undergraduate biology.

Page Summary

The five kingdoms classification organizes all living organisms into Monera, Protista, Fungi, Plantae, and Animalia based on structure, nutrition, and reproduction. This model aids students and researchers in understanding biodiversity and evolution. For comprehensive learning and exam success, Vedantu provides curated resources covering definitions, diagrams, differences, and MCQs.

FAQs on What Is the Five Kingdoms Classification?

1. What is the Five Kingdoms classification?

The Five Kingdoms classification is a biological system that organizes all living organisms into five major groups based on similarities in structure, function, and evolutionary history.

The five kingdoms are:

- Monera (prokaryotes: bacteria and cyanobacteria)

- Protista (unicellular eukaryotes)

- Fungi (multicellular and unicellular saprophytes)

- Plantae (multicellular, photosynthetic plants)

- Animalia (multicellular animals)

2. Who proposed the Five Kingdom classification system?

R.H. Whittaker proposed the Five Kingdom classification in 1969.

- He grouped organisms into Monera, Protista, Fungi, Plantae, and Animalia

- This classification was based on cell structure, mode of nutrition, and complexity of organisms

3. What are the main features of Monera in the Five Kingdom system?

Organisms classified under Monera are prokaryotic, simple, and unicellular.

Key features:

- No nucleus (nucleoid present instead)

- Lack membrane-bound organelles

- Examples: Bacteria and Cyanobacteria

4. Explain the characteristics of Protista according to Whittaker's classification.

The kingdom Protista includes simple, mostly unicellular eukaryotic organisms.

- Possess a true nucleus and membrane-bound organelles

- Exhibit both autotrophic (like algae) and heterotrophic (like protozoa) modes of nutrition

- Examples: Amoeba, Paramecium, Euglena

5. What distinguishes Fungi from other kingdoms in the Five Kingdom classification?

The Fungi Kingdom is defined by its unique mode of nutrition and cell structure.

- Fungi are mostly multicellular, eukaryotic, and lack chlorophyll

- They absorb nutrients from dead organic matter (saprophytic)

- Cell walls are made of chitin

- Examples include mushrooms, yeast, and moulds

6. What are the criteria used by Whittaker to classify organisms into five kingdoms?

Whittaker used three main criteria to classify organisms in the Five Kingdom system:

- Cell structure: Prokaryotic or Eukaryotic

- Mode of nutrition: Autotrophic (photosynthetic), heterotrophic (ingestion, absorption)

- Organizational level: Unicellular or multicellular

7. Why was the Five Kingdom classification system developed?

The Five Kingdom classification system was developed to overcome limitations of earlier classification methods.

- Earlier systems (2-kingdom and 3-kingdom) failed to consider fundamental differences, such as cell structure and modes of nutrition

- Whittaker’s system better reflects evolutionary relationships and organism diversity

8. What are the main differences between Plantae and Animalia kingdoms?

Plantae and Animalia kingdoms differ in their basic characteristics.

Plantae:

- Multicellular, eukaryotic

- Contain chlorophyll and perform photosynthesis (autotrophic)

- Cell wall present

- Multicellular, eukaryotic

- Do not have cell walls or chlorophyll

- Heterotrophic mode of nutrition (ingestion)

9. List five organisms that belong to different kingdoms as per the Five Kingdom classification.

The Five Kingdom system groups various representative organisms under each kingdom.

- Monera: Escherichia coli

- Protista: Amoeba

- Fungi: Rhizopus (bread mould)

- Plantae: Mango tree

- Animalia: Frog

10. What are the advantages and limitations of the Five Kingdom classification?

The Five Kingdom classification offers clearer organization but also has some drawbacks.

Advantages:

- Considers cell structure, nutrition, and organizational complexity

- Better reflects evolutionary trends

- More precise for classifying microorganisms

- Viruses are not included in this system

- Some organisms show characteristics of more than one kingdom